Alchemy

Alchemy is not a religion it is a spiritual philosophy and a science, it has no holy book and no places of worship. There are no books of instruction on how to become an Alchemist, there are no rules and you don’t need to be a chemist, just a longing to be enlightened is enough.

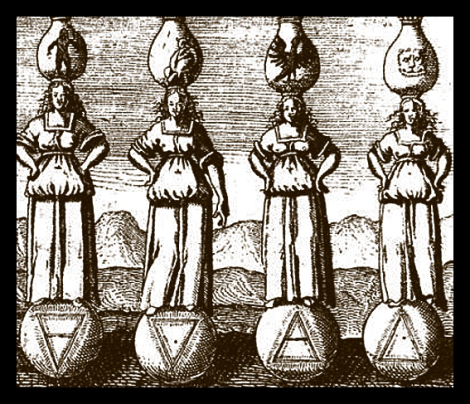

Nothing is so misunderstood as the four elements of Alchemy, as they do not and never did represent the chemical elements of modern science. Earth, air, fire and water are the elements that cause change on the planet and Alchemy is about controlled changes.

Referred to as causality or causation by scientific academia, cause and effect are derived directly from Alchemy. Much of what is called modern science originally had an alchemical source. Transmutation is change and is not restricted just to the manufacture of gold.

John Frederick Helvetius, witnesses transmutation: “The Golden Calf, Which the World Adores and Desires: In which is handled The most Rare and Incomparable Wonder of Nature, in Transmuting Metals; viz. How the intire Substance of

Lead, was in one Moment Transmuted into Gold-Obrizon, with an exceeding small particle of the true Philosophick Stone. At the Hague. In the year 1666. Written in Latin by John Frederick Helvetius, Doctor and Practitioner of Medicine at the Hague, and faithfully Englished.

London, Printed for John Starkey at the Mitre in Fleetstreet near Temple-Barr, 1670.

129 pages. 142x82mm.” http://www.alchemywebsite.com/eng_h_l.html

“Why are there artifacts of gold in the British Museum supposedly produced by transmutation(15)? Why are these specimens exponentially more pure than the technology of their respective ages usually produced? Why are there so many eye witness accounts of transmutation? Why did an Imperial Edict in 144 B.C. China decree public execution for anyone caught preparing gold by alchemical means? Why did the Roman Emperor Diocletian order the burning of all Egyptian alchemical manuscripts in 290 A.D.? Why also did Henry IV outlaw the alchemical production of gold in sixteenth century England?” http://www.levity.com/alchemy/caezza4.html

A Chart of Alchemical Correspondences

http://www.alchemylab.com/correspondences.htm

Alchemy Electronic Dictionary

http://www.alchemylab.com/dictionary.htm

Michael SENDIVOGIUS – Alexander SETON

The New Chemical Light

http://www.rexresearch.com/alchemy/newchem.htm

The Kybalion PDF Basic alchemical wisdom.

http://www.hermetics.org/pdf/kybalion.pdf

Or read The Kybalion online:

http://www.gnostic.org/kybalionhtm/kybalion.htm

“Far Journeys”: THE MYSTERY OF LOOSH By Robert A. Monroe. http://tinfoilpalace.eamped.com/2012/07/09/nexus-magazine-free-articles-online/

The Grail Quest and The Destiny of Man

Part V-c: The Fulcanelli Phenomenon

Laura Knight-Jadczyk

http://cassiopaea.org/cass/grail_5e.htm

For the academic mind: Interpreting Representative Texts and Images, Karen-Claire Voss

http://www.istanbul-yes-istanbul.co.uk/alchemy/Spiritual%20Alchemy.htm

Presented to the Amsterdam Summer University: “Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times.” August 15-August 19, 1994. This is a slightly revised and augmented version of what appeared in Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times, ed. by R. van den Broek and W.J. Hanegraaff. State University of New York Press: New York, 1998

Alchemy is of interest to the historian of science because of its bearing on the development of modern chemistry, but it is also of special interest to the historian of religions, because it represents a centrally important current within the western esoteric tradition. [1] That tradition was, and still is, as Antoine Faivre expressed it so beautifully, “both a way of life and an exercise of vision.” [2] I recall this characterization here to emphasize the fact that the esoteric tradition and the various currents of which it is comprised are not merely historical artifacts but have always been, and continue to be, dynamic, vital actualizations of the human spirit. The texts and the iconography of spiritual alchemy are replete with images that attest to that vitality. It is for this reason that I do not attempt to trace the development of what I am calling spiritual alchemy (a distinction that is explained below) in a chronological way. Besides, this has already been done in several easily accessible overviews. [3] My approach will be to treat it as an integral whole, one that escapes what Mircea Eliade (one of the noted commentators on the subject) described as the terror of history. [4]

In my view, the greatest mistake one can make in approaching spiritual alchemy is to come to it with a set of preconceived doctrines concerning the nature of things, which is allowed to function axiomatically. The task then becomes no longer that of trying to understand, but of attempting to valorize or to vilify. While one thing such an approach to spiritual alchemy lacks is subtlety, but there is an alternative approach that is potentially very subtle indeed, because it may easily function as a disguised form of the first, albeit unintentionally. This second approach runs the risk of subjecting the materials being examined to the tacit, and hence unexamined, criteria embedded in a mentality, a world view, a conceptual framework, which are such that the materials appear as rattling, dry bones, devoid of meaning, perhaps thereby even faintly ridiculous. This often occurs when we utilize an approach found in much late-twentieth-century scholarship, comprised of idiosyncratically (hence, arbitrarily) selected elements from the analytic philosophical tradition, together with the tattered, tired (thought still feebly twitching) remnants of ideas of objectivity that were developed in the late nineteenth century. Great care must be taken when utilizing such contemporary methodological tools to examine materials like alchemy. Instead, one should try to become intimately familiar with the pre-modernist worldview that gave rise to spiritual alchemy and to develop a genuinely empathetic grasp of both the world-view and its manifestation. Without these two efforts we cannot hope to understand the materials. This approach is not to be confused with advocacy or with depreciation; rather, it is related to a third thing: it requires courage. For a scholar, bracketing experience is much easier, and certainly much safer, than to confront it head on. Put very simply, the approach I am using here leaves one open to the possibility of experiencing wonder: of coming to know something we did not know previously, or of deepening our knowledge of something we were already acquainted with. That is my understanding of what being a scholar is essentially all about, and I confess that it is a process that brings me not only pleasure, but joy.

A good example of what I understand by becoming familiar with a particular world-view appears in Robert Darnton’s introduction to his book, Mesmerism and the End of the Enlightenment in France. Darnton can hardly be viewed as an apologist with some particular axe to grind; his work can only evoke admiration. Darnton writes that his book “attempts to examine the mentality of literate Frenchmen on the eve of the Revolution, to see the world as they saw it . . . ” Although such a “presumptuous undertaking must fail . . . it is worth attempting.” His research has lead him to conclude that the “hottest topic” of this period was “science in general, mesmerism in particular,” and he says that “Frenchmen of the 1780’s . . . found that mesmerism offered a serious explanation of Nature, of her wonderful, invisible forces, and even, in some cases, of the forces governing society and politics.” Darnton adds that it is just too bad for modern readers if they find this fact unpalatable. Accordingly, he writes, his aim is to “restore [Mesmer] to his rightful place, somewhere near Turgot, Franklin, and Cagliostro in the pantheon of that age’s most talked-about men.” [5]

It is clear that in the case of spiritual alchemy we have a somewhat analogous situation. It is not only appropriate to discuss an alchemical treatise in terms of the worldview which formed the context within such a treatise was produced; this is even required, lest we distort the very material we seek to understand. The worldview which produced the particular corpus of material to which I am referring as “spiritual alchemy” was that of esotericism. Let us therefore begin with examining some of the most important elements of that worldview.

The World-View of Esotericism

According to the taxonomy devised by Antoine Faivre, the simultaneous presence of four “intrinsic” components or characteristics is the criterion which renders esotericism identifiable; these four are sometimes, though not necessarily, accompanied by two more, which he calls “relative.” [6] To summarize very briefly, the first is that of the doctrine of correspondences that holds that all things in the universe are interrelated. The idea that there is a relationship between the microcosm and the macrocosm is part of this. Because of that interrelationship every thing can, to a greater or lesser extent, influence, or be influenced by, every other thing. The second is that of “living Nature,” meaning the idea that Nature is dynamic, multi-level, and multivalent. Everything in Nature is a potentially ephiphanic sign, whence is derived, for example, Henry Corbin’s lyrical reference to the Sufic experience of Nature as une grande thophanie.” The third characteristic pertains to a very precise form of imagination [7] and mediation. All elements in the universe are interrelated by means of things that intrinsically possess a mediating character (i.e., by means of divinities like Hermes, so beloved of the alchemists, [8] and what might be called “semi-divinities,” (inasmuch as they have their being between two worlds and access to both, like angels); or by means of things within which a mediating quality is thought to inhere, or which can be imbued with that quality, i.e., by somehow being pressed into the service of performing the function of mediation (e.g., images, mandalas, texts, rituals, etc.) [9] The fourth component is called “transmutation”: a term that is derived directly from alchemy. As explained by Faivre, this term is preferable to “transformation,” since the latter “does not necessarily signify the passage from one plane to another, or the modification of the subject in its very being, i.e., ontologically.” [10] ‘Transmutation’ means metamorphosis, and entails a form of gnosis.” Together with the idea of transmutation,” Faivres characterization of esotericism as both a way of life and an exercise of vision raises important theoretical considerations that have a direct bearing on understanding what I am calling spiritual alchemy. In an early article to which I am greatly indebted, Faivre has discussed some of the same issues (e.g., the subject/object relation and the alchemical movement from potency to act) that I take up here. However, to my knowledge all of the aforementioned considerations have not been raised, still less developed, nor have their implications been examined in the specific context of the study of esotericism. I will begin developing these ideas in the following section and continue in the course of examining the texts and images I have selected. My approach to spiritual alchemy (and by extrapolation to esotericism) follows the general approach of authors such as Mircea Eliade. [11]

I said that spiritual alchemy must be approached in terms of the world-view that gave rise to it; and I mentioned the importance of realizing just how different that world-view is from the one prevailing today. Consider, for example, Leo Stavenhagen’s statement in his edition of the dialogues of Morienus and Khalid ibn Yazid:

Alchemy has suffered the misfortune of being classed as a science from a modern point of view–as a chrysopoietic technology–which has occluded our view of its system. Scientific it certainly was when it first reached the West sometime late in the twelfth century, but in a thoroughly medieval sense, in which nothing, science least of all, could be separated from ethics, morals, and religion. For if science could not substantiate man’s claim on immortality, what use was it? [12]

The practitioners of spiritual alchemy based the validity on (what they considered to be) the fact that they experienced transmutation, and/or had a vision or revelation that resulted in an experience of transmutation. Their reasoning was that one can only experience things that are real; and experience, for them, was something that has integrity, that can and should be trusted. In sum, experience provided both the criterion and the authority for making the claim that their worldview was valid.

In contemporary usage, the term worldview mostly performs a distancing function: it is used to refer to a set of beliefs, doctrines, or philosophical ideas. However, when we say that the alchemists held a particular worldview for which they claimed validity, we cannot meant that they merely held a set of beliefs about the world, or that they merely accepted a set of ideas concerning the world on an intellectual level. Rather, in their context, they claimed that their worldview was immediately derived from an actual experience of the four things that Faivre has called intrinsic components, which make the esoteric tradition identifiable (to us), and render the esoteric worldview coherent (in terms of our perspective). These four things were experienced as real, i.e., as deriving from the nature of reality itself. To have a worldview both implied and entailed, for the alchemists, a specific experience of the world. That experience of the world not only gave rise to the beliefs, doctrines, or philosophical ideas, but also supported a praxis that was consistent, congruent, with the worldview. Theory and practice were inextricably woven together. This is why the materials of spiritual alchemy indeed constitute compendia of techniques “of illumination,” [13] written with the intention of making accessible to others a way of being in the world, and this is the reason why spiritual alchemy was believed to function as a mode of transmitting gnosis. In short, the spiritual alchemist was an initiate, one who knows. [14] .

A Framework for Understanding

The term “spiritual alchemy” is a precise designation that I chose using the same distinguishing that were used by the alchemists themselves. An alternative form, material alchemy, was practiced by those who were often referred to as puffers. Originally, this term simply referred to the efforts with bellows that were needed to keep the fires going. Eventually, however, it came to acquire disparaging connotations; it was used by one group of alchemists to refer to another, i.e., to those who were engaged in a mere pseudo-alchemy and whose insight into the nature of the alchemical process never extended beyond the material. [15] Puffers” maintained that the Philosopher’s Stone was material gold, and only that. They were in the work for the money, or they were in it in order to increase the store of facts that were then available, or both. In contrast to this, “spiritual” alchemy was understood as a form of illumination, a means of transmutation, a method for experiencing levels of reality that are not ordinarily accessible, since they exist beyond the level of everyday reality. “Material alchemy” utilizes substances from the physical world and has for its goal some product or other (e.g., gold or knowledge). “Spiritual alchemy,” in contrast, works with physical substances too, but in a very particular way: one that is “spiritual” in that it includes all of the characteristics of material alchemy, and also goes beyond them, to an experience of transmutation resulting in an ontological change. Alchemists who practiced spiritual alchemy would be the first to insist that, strictly speaking, there is not other kind of alchemy. Whether or not they were correct in this is not for us to decide; but for the sake of brevity, henceforth in this paper I will refer to spiritual alchemy simply as alchemy.

Below, I will provide an overview of the alchemical process. First, however, I want to set forth a partly theoretical, partly descriptive account in order to afford some preliminary help with understanding. In what follows I give an account of the alchemical process that presents, first, a description of three characteristics that permit us to distinguish these two types of alchemy (i.e., the experience and concept of the subject/object relation; causality; and time) and second, a summary of changes that took place in an alchemists conceptual model as the work progressed. [16] For the sake of clarity and brevity, each of the three characteristics has been more or less artificially separated from the other two, although in fact of course each is related to the others in exceedingly complex ways.

Here are the three characteristics:

1. Subject/object relation. Both types of alchemy exhibit a characteristic experience and concept of the subject/object relation. In material alchemy one conceives reality as an object completely removed from oneself, outside oneself; hence, what we call the self is the subject, what we call the world is the object, and the boundary between subject and object is static, fixed. In spiritual alchemy, however, one finds reality to be a living system in which one participates, to which one contributes, and in which the boundaries between subject and object are fluid.

2. Causality. Both types of alchemy exhibit a characteristic experience and concept of causality. Material alchemy is characterized by what one can call substance or mechanistic causality. This is the kind of causality associated with a “means/ends” approach to reality, one that holds that reality is comprised of only one level and that all of its elements can be manipulated as one manipulates a machine–for example, a lawn mower. Spiritual alchemy, however, is characterized by what one can call process causality, the kind that Giordano Bruno had in mind when writing about the “inner artificer”. [17] At the level of conceptualization, the operative causality in spiritual alchemy is understood to possess an infinite number of gradations of the movement from potency to act, which can be modeled (albeit inadequately) [18] as a spectrum marked at one end by absolute potentialization and at the other by absolute actualization. [19]

3. Time. The theme of the acceleration of time in alchemy has been discussed at length by Eliade, and I do not intend to do more than mention it here. [20] The basic idea is that telluric processes that took aeons to accomplish within the earth could be radically accelerated in the alchemical laboratory. Here I simply wish to call attention to a contrast that can be perceived between the conception of time in material alchemy and in spiritual alchemy. In material alchemy one generally finds a conventional conception of time as being comprised of three discrete “parts”: past, present, future. Moreover, time is considered irreversible; it flows in one direction only. In spiritual alchemy one finds a much more subtle conception of time in which these three discrete parts are only apparently separated from each other. In spiritual alchemy, time is not experienced as irreversible, but reversible; not only that, but in spiritual alchemy the “movement” of time is not so much a movement as a mode of perception, [21] and thus goes far beyond being something which can be conceived of in linear terms, as having a forward or backward motion that could be modeled as occurring on an imaginary line.

I have described these three characteristics for the sake of completion, but in this paper, most of the emphasis will be on the first two.

Having outlined these three basic characteristics, I will now give a summary of the changes that took place in the alchemists conceptual model during the course of the work. The conceptual model with which both material and spiritual alchemy began was linear. The goal of the alchemical process was located at the end of a linear series of discrete pairs of causes and effects; the operative causality was conceived of as substance causality. The initial conception of the subject/object relation is evident in the view of the goal as external and unrelated to the alchemist. It can be diagramed thus:

The first modification to which this model could be subjected is related for the most part to causality. The conception of the operative causality would change from from substance causality to process causality. The task of resolving the elements in the alchemical opposition was considered so formidable that the alchemists were convinced that they could not possibly effect a resolution by themselves. The alchemical Mercurius began to be understood as a kind of divine other who would intervene in the work by effecting the resolution of opposites. However, notwithstanding the introduction of Mercurius as an operative factor, the alchemical work would continue to be modeled in a linear way, meaning that the subject/object relation would continue to be conceived of in the same way as before. The second model remained linear, like the first, save for a new understanding of Mercurius as process (along with a burgeoning intuition that the goals was somehow identical with the starting point, symbolically equivalent to the prima materia of cosmogonic myth). That model can be diagramed as follows:

The next modification is very radical because it entails a change in the conception of the entire alchemical work. To begin with, the conception of causality as process is retained, but now the linear model would be replaced by a circular one reflecting new insight into the nature of the alchemical process. [22] I have described this modification as radical because of its profound implications for the conception and the experience of the subject/object relation, causality, and possibly (although not necessarily) time, and if it were possible to posit a strict demarcation between material and spiritual alchemy one would do it at this juncture. It can be diagramed as follows:

Let me try to explain. Many of the alchemists explicitly identified themselves with mythic creators as they struggled with unformed materials and understood their work as being analogous with that of Terra Mater. Both identifications can be interpreted as being an imitation, a re-creation of sacred processes. I suggest that the extent to which an alchemist subscribed to such an identification and was able to shift away from the normal experience of space, time, and historical process determined the extent to which he or she made a shift away from an ordinary mode of conceptualization and experience and its concomitants (that shown in the first diagram) toward an extraordinary mode (that shown in the last diagram). In Eliadean terms, we might say that profane experience would become increasingly sacralized. The reason I have described this modification as extremely radical is because we are dealing here with no less than the progressive dissolution of normal, dichotomized categories, a shift from the ordinary mode of individual, bounded consciousness to one that was (as I have already said) symbolically equivalent to the prima materia of the beginning; to put it in alchemical terms, at a certain pint in the alchemical work the alchemists saw that it was necessary for Mercurius to intervene in order to unite the opposites; indeed, by the end of the alchemical work, a whole series of opposites would have to be united by Mercurius. He would transform the two elements within each opposition into one another, until they converged on a central point (e.g., the central axis of the caduceus, or the sacred center where heaven and earth meet). The accompanying line of reasoning was that on the most profound level, the alchemist equaled both the alchemical process and the means of the process; alchemical process was tantamount to both self-knowledge and to the knowledge of the divine; [23] and the goal of the alchemical process was somehow equivalent to the starting point, the prima materia.

The Alchemical Process

I have said that the alchemical texts reflect an understanding of validity based on experience, that they were intended as techniques of illumination, thereby involving theory as well as praxis, and that over the course of the alchemical work, there were radical alterations in the conception and the experience of the subject/object relation, causality, and time, resulting in the transmutation of the alchemist himself. Before turning to the treatises themselves, I will provide an overview of the alchemical process. We must realize, however, that the various divisions to which I will refer (just as the characteristics and the conceptual models that I have already outlined) are useful only as general heuristic tools. Beyond that, they become artificial and forced, and ultimately misleading, since they refer to phenomena and process that are interrelated in extremely complex ways.

Alchemy can be understood in terms of two aspects which Carl Gustav Jung has referred to as the “double face of alchemy” –the operatio (the practical) and the theoria (the theoretical). Every alchemist equipped a laboratory, selected and studied texts, and constructed a theoretical framework (which was continuously refined) to reflect the alchemists’ conception and experience of the process, as well as his or her relationship to it, both of which changed as the work proceeded. On one level, the alchemists’ purpose in the laboratory was the production of gold, the most perfect of all metals; on another level, their goal was to produce the arcane substance known as the Philosopher’s Stone. [24] With respect to alchemy’s practical aspect, it is virtually impossible to determine the exact order or number of stages in the alchemical work, and it is not always apparent what level is being referred to. For example, we may be told that mercury is necessary for a certain procedure, but this might mean the metal that is meant, or the qualities of the metal, or the divinity, or even all three. For a variety of reasons, primarily because of the doctrines of correspondences and similitudes which were linked to the belief in the relation between microcosm and macrocosm, the alchemists were given to making analogies between that which occurred on an “outer,” material level, and experiences which took place on an “inner,” spiritual plane. [25] Thus, an analogy was made between the maturation of the chemical processes in the alchemists’ laboratory that would result in the Philosopher’s Stone, and the development of their own gnosis. If, on the material level, the alchemists’ purpose in the laboratory was the production of gold, the most perfect of all metals by actualizing all the qualities of gold which were thought to be potentially present in lesser metals, on the spiritual level it was to develop the true Self, to “lead out the gold within,” as they said, by actualizing the qualities potentially present in the human being.

The alchemical work has three basic stages: the nigredo, the albedo, and the rubedo. It is true that other stages corresponding to nuances of the alchemical process are mentioned in the texts but, although these would be of the utmost importance for an alchemist, they are not so critical for us. [26] The essence of the alchemical movement is contained in the oft-quoted motto: “solve et coagula”, “divide and unite.” Like the three stages discussed above, these two movements are essential to the work and comprise cycles that are repeated over and over again, on increasingly subtle levels. Alchemy aimed at the resolution of material and spiritual opposites as conventionally understood. This resolution took place on different levels, corresponding to deepening levels of understanding of the true nature of the alchemical work. At a certain point a mediating term, often under the form of the alchemical Mercurius, would intervene in the process. The ultimate resolution was characterized by a mode of subtle mutual reciprocity and interpenetration in which each term of an opposition entered fully into the being of the other, simultaneously present to the other, transforming and being transformed. This union was frequently imaged as a hieros gamos, and its fruit was the Philosopher’s Stone.

1. The nigredo is the preparatory stage when the alchemist must confront unknown, chaotic material. Much has been written (most notably by C. G. Jung and Mircea Eliade) about the analogy between the alchemists, who must grapple with the chaos of the prima materia as a prerequisite to creation, and mythic creator divinities. In the most general terms, the nigredo means a first encounter with darkness, with depth. Symbolically analogous with probing the innermost depths of Tella Mater, in order to find the Philosopher’s Stone, and claim it as the prize, [27] the nigredo is an encounter with the self, the time of the dark night of the soul, when there is no certainty to be found anywhere. It is at this stage that the alchemist must plunge into the disorganized, confused welter of material, with no clear instruction. On the level of material process, this stage is associated with blackness; on the level of spiritual process it is associated with melancholy of the extreme Saturnian type. [28] One early seventeenth-century engraving depicts an alchemist kneeling within an alcove that is set apart from the rest of his laboratory. [29]

His kneeling position and outstretched, supplicating arms give mute testimony to the interrelatedness of the concepts and experience of “spiritual” and “material.” This is implicit in the word “laboratory,” which is derived the Latin “laborare,” “to work,” and “orare,” to pray. For the alchemist, doing the former without the latter would have been unthinkable. [30] At the same time, this image not only testifies to the depression and despair that plagues the alchemist as he seeks to impose form on the chaos that confronts him, but also to the fact that he is still seeking help from outside himself. Thus, it is an indication that the changes related to the subject/object relation and the causality operative in the work have not yet begun.

2. The next stage is the albedo. With the aim of imposing norms on chaotic material, the alchemists approached the massa confusa of the primal substance by dividing it. Throughout the albedo stage they continued to work with the various elements that were derived during the nigredo, and by the end of the albedo they were left with two elements viewed as though in polar opposition to one another. It is here that the alchemical problem of the coincidentia oppositorum arises. Now the task was to effect a successful resolution in order to obtain the Philosopher’s Stone. This resolution had to be carried out on many different levels, as indicated by the symbolic representations of pairs of opposites as both material and spiritual; e.g., silver/gold and body/spirit. Once again, these levels correspond to deepening levels of understanding with regard to the true nature of the work. Finally, according to alchemical theory, all the opposing elements would be resolved, all the levels would somehow converge on one another, and the goal would be achieved.

As explained above, the conceptual framework underwent changes at different points in the alchemical work. At the end of the albedo stage we can observe the first of them. While the model remains linear, there is a new conception of causality that reflects a new understanding of causality reflects a new understanding of the significance of the image of Mercurius. While we cannot begin to do justice to the significance of this figure here, it will help to think of Mercurius as a kind of personification of innumerable paradoxical qualities that would provide the alchemists with the means of the work. [31] As the means of the work–i.e., as the process that effected transmutation–Mercurius functioned as the third term that would bring about a resolution of opposites simultaneously in both the substances and the alchemist. The condensed material, left over from the distillation that took place during the albedo stage, corresponded to the spirit, while the substance from which it had been extracted corresponded to matter, the body. Now that the soul had been “led out” from the body, there remained the problem of conflict between them. The substances could not be merely superficially reunited; instead it was necessary to produce a genuine compound. That compound signified the resolution of opposites, which the alchemists believed could not take place with spiritual help of some sort. Hence, Mercurius would come to resolve the problem by effecting a synthesis. At this stage, the concept of the subject/object relation had not yet changed, but once the understanding of the work as a linear series of single, discrete, and substantial causes and effects was mitigated by the addition of Mercurius it is an indication that the concept of the operative causality is beginning to change from substance to process causality. The model of the work is now a linear chain of substantial causes and substantial effects in which Mercurius will intervene so as to effect a synthesis among the various pairs of oppositions. The reason for saying that the concept of the work as a whole remained essentially linear is because Mercurius is still viewed as an object relative to the alchemist, i.e., as an external force that would enable the alchemical work to proceed. The goal was still thought of as being an object that would be reached only at the end of the alchemical stages. Thus, at the beginning of the third stage, the rubedo the elements of the coincidentia oppositorum had still to be resolved, via Mercurius, the personification of mediating energy, the third term. While the thrust of the first and second stages involved a movement aimed at division; the essential movement in the third stage is one that emphasizes unity. One of the processes of this stage was referred to as the coniunctio. The aim of the rubedo was to join together the two elements left over from the previous stages, and the product of the union would be the Philosopher’s Stone. As I explained, at the end of the albedo the conception of causality began to move from substance to process, but Mercurius continued to be thought of as the external cause of the work. Here a linear discussion of the stages that involves discussing each of them separately, before going on to discuss the Philosopher’s Stone, breaks down. There are extremely complex issues involved with these changes. One of them is that Mercurius (hitherto regarded as the cause of the work) begins to become identified with the alchemist herself and with the goal of the work. This means that the concept of the subject/object relation changes. The diagram provided above is an appropriate model of the alchemical work at this stage, because it reflects the notion of process as well as the circularity that reflects these new insights into the nature of the work.

The successful end to the quest for the Philosopher’s Stone, which the alchemists initially regarded as external and “other” to themselves, was spoken of as a return to the prima materia. Some years ago, I wrote that the alchemical model appears to have been based on the “myth of the eternal return,” the idea that reality consists of an endless, cyclical repetition of events. I argued that, in a certain sense, the idea of a return (modeled by the circle whose circumference is outlined with a waving line) is almost as limiting as the two preceding models. I further argued that if any alchemist had reached the goal of the alchemical work, he or she would not have interpreted the experience in terms of a return to the prima materia. I reasoned that since a return is diachronic, it excludes the possibility of a synchronic experience of the totality. That the alchemists spoke of their attainment in terms of it being a return clearly indicates that their concept of time had undergone some changes: time had become reversible. The problem is that the idea of a return to the prima materia indicates that, even though time is no longer considered irreversible, but reversible, we are still dealing with a linear concept of time. I argued that not only was this an indication that a new model was needed (I suggested a spiral), but it was an indication that the alchemists in question needed to have gone further. [32] Now I think that what is needed is a much closer look at what was meant by the language about a return to the prima materia. If we think of the Stone as the fruit of two elements extracted from out of the chaos of the beginning of the work, which subsequently underwent processes that resulted in their becoming whole again, this is certainly one explanation for the meaning of the Child of the Work, as it appears under the image of the Hermetic Androgyne, and the rubric “Two-in-One.” However, the Stone is more than simply the sum of its parts, derived at the end of a series of operations. It is, rather, an emergent property derived from a multi-leveled union of the two. The Child of the Work necessarily continues to participate in the being of the two, just as the two continue to participate in the one from which they merge; yet it goes beyond them, and becomes a third thing. For this reason, it is more precise to speak of a “Three-in-One.” It is on this basis that one can gain a deeper insight into what it really means to say that the beginning and the end are one. [33] The image of the Child of the Work signifies the second birth in the theosophical sense. [34] The alchemist arrives at his/her goal after a long and arduous journey, involving not only the combination and re-combination of elements that were already extant within, but the integration of new elements as well. On one level, these appear to originate from without but on another level, they are already potentially extant. Ultimately the alchemist discovers that the Child is his or her true Self. In the context of spiritual alchemy, we must grapple with a nuanced aggregate of previously disparate conceptual categories reflecting equally nuanced experience. At this point, our methodological and conceptual tools are pushed to the limits. Here, too, we reach the limits of metaphorical as well as analytic language, and, possibly, even the limits of our own experience.

Selected Texts

I have selected four treatises that are representative of spiritual alchemy; two of them texts have images. The first treatise illustrates the importance accorded to personal experience; the last three illustrate the changes connected with the subject/object relation, causality, and time. I will concentrate on the discursive and pictorial images that show the coincidentia oppositorum under the form of the hieros gamos since these are excellent indicators of change in the conceptualization and experience of the subject/object relation.

The Revelations of Morienus to Khalid ibn Yazid

The first alchemical work to appear in the West was a treatise attributed, like many others, to Hermes Trismegistus. According to Leo Stavenhagen, this attribution derives from Robertus Castrenis, who translated the text from Arabic into Latin in 1182. It was later published in Paris, in 1559, under the title: “Booklet of Morienus Romanus, of old the Hermit of Jerusalem, on the Transfiguration of the Metals and the Whole of the Ancient Philosophers’ Occult Arts, Never Before Published.” [35]

The story concerns Khalid, a king who had looked for many years for a man described as “Morienus the Greek, who lived as a recluse in the mountains of Jerusalem,” because he wanted to find out from him the secret of the “Great Work.” The king has occasion to travel to another town, where a man comes to him and tells him that he has made his home in the mountains of Jerusalem and knows a wise man, a recluse, who possesses the knowledge that the king is looking for. After warning the man about the punishment he can expect if it turns out that he is lying, the king gives him many gifts and arranges for him to lead an expedition in search for the wise man. The narrator Ghalib, who accompanies the expedition, relates how they finally succeed in finding the wise man. He was tall of stature, though aged, we read, and although lean, so noble of countenance and visage that he was a marvel to behold. Yet he wore a hair shirt, the marks of which were borne on his skin. [36] At their bidding, he agrees to come to the court for an audience with the king. When the king asks the man his name the answer comes: “I am called Morienus the Greek.” The king asks how long he has lived in the mountains and learns that Morienus has been there for over one hundred and fifty years. Well pleased with this stranger, the king gives Morienus his own quarters and begins to visit him twice every day. They speak of many things, and grow very close. Finally, one day the king asks Morienus to tell him about the Great Work. Seeing that the king is worthy of this, Morienus tells him that he has achieved initiation, and agrees to instruct him, emphasizing that nothing can be achieved if it is counter to divine will. He speaks of how God “chose to select certain ones to seek after the knowledge he had established,” and how over time this knowledge has been lost, save for what remains in a very few books, which are difficult to understand, since the “ancients” sought to preserve the secrets “in order to confute fools in their evil intentions.” Because this knowledge was “disguised,” anyone seeking to “learn it must understand their maxims.” Morienus begins to emphasize that the Work is but a single thing.

Now in answer to your question as to whether this operation has one root or many, know that it has but one, and but one matter and one substance of which and with which alone it is done, nor is anything added to it or subtracted from it. [37]

Numerous authorities, including Hermes, Moses, Maria, and Zosimos, are cited throughout by Morienus to legitimate what he says, and the lesson concerning oneness is reiterated continually. There is but one stage and one path necessary for its mastery. Although all the authorities used different names and maxims, they meant to refer to but one thing, one path and one stage. The method to be followed is in imitation of Nature, and like Nature, is characterized by process causality:

For the conduct of this operation, you must have pairing, production of offspring, pregnancy, birth, and rearing . . . the performance of this composition is likened to the generation of man, whom the great Creator most high made not after the manner in which a house is constructed nor as anything else which is built by the hand of man. For a house is built by setting one object upon another, but man is not made of objects. [38]

Morienus then proceeds to instruct the king about the details of the substances to choose, the proportions, how to mix them, when to heat them and for how long, always repeating that God’s help is needed. He insists on the need for personal experience and tells the king that before he will continue with his explanations, he will bring before [him] the things called by these names: that you may see them, as well as work with them in your presence. . . one who has seen this operation performed, is not as one who has sought for it only through books . . . [39] Finally, he says, that “there is no strength nor help except by the will of great God most high,” and the narrator writes: “Here ends the book of Morienus, as it is called. Thanks be to God.” [40]

This treatise is paradigmatic of the way in which validity and the authority of experience are bound up with each other in the alchemical tradition. Initially, Morienus is able to win the trust of the king solely on the basis of the answers he gives to questions concerning his personal experience during his first audience with the king. Later, Morienus tells the king that before he proceeds with instruction, he will perform various steps while the king watches, “so that you may see them”, since “one who has seen this operation performed, is not as one who has sought for it only through books.”

Rosarium philosophorum

The first printed edition of the Rosarium philosophorum appears in a collective work, Alchimia opuscula complura veterum philosophorum (…), that came out in Frankfurt in 1550. [41] The text is accompanied by twenty images (plus one on the title page). With respect to the idea that experience is the most important criterion for claiming validity, the Rosarium states that there is only “one stone, one medicine, one vessel, one regiment, and one disposition, and know this: that it is a most true Art.” This is immediately followed by what is intended to be the capstone argument: “Furthermore the Philosophers would never have laboured and studied to express such diversities of colours and the order of them unless they had seen and felt them.” [42]

While the text of the Rosarium is rich, I find the images even more compelling, since they convey better than the text the most important theme in alchemy: that of the conjunction of opposites. In the Rosarium, just as in so many other alchemical treatises, this theme appears under the form of the hieros gamos. C. G. Jung considers the images of the Rosarium philosophorum to be paradigmatic, and says that they constitute the “most complete and simplest illustration” of the importance of the hieros gamos in alchemy. [43] In an earlier article about the hieros gamos in the context of the history of religions, I discussed some of the implications of its appearance in the images of the Rosarium. I argued that many of the alchemists appear to have undergone a complex experience involving mutual reciprocity between the events in the laboratory and within themselves, of a kind that hearkens back to, and carries forward, the imprint of a religious tradition that combined physical and spiritual levels of transformation [44] and that texts like that of the Rosarium attest to this. Here I wish to emphasize that the alchemical conjunction under the form of the hieros gamos is itself illustrative of the changing conception and experience of the subject/object relation, causality, and time.

Plate 1 shows a fountain with three spigots. As the text explains, although it appears that the waters flowing from each of them are separate, they are really a single water “of which and with which our magistery is effected.’ One may note the conflation between substance and method that is implicit here. Thus, there are implications for the conventional subject/object relation from the very beginning. Elsewhere I have compared these flowing waters to the image of primordial waters from the Enuma elis, a creation myth dating from c. 1900 B.C.E., which tells how the primordial waters of Tiamat, the female principle, commingle as a single body with those of Apsu, the male principle; in that context, I argued that the theme of the hieros gamos is implicitly present already in this first image. [45] Like the primordial hierogamy from which all life sprang, the alchemical fountain is also the source of life.

In plate 2 we see a king and queen dressed in elaborate robes. Each holds out to the other the end of a stalk terminating in two flowers; he stands on the sun, she on the crescent moon. At this stage they are separate, but their union in the ‘chymical marriage’ is symbolically prefigured by their clasped hands. A dove (at once a mediating symbol as well as a further link with the hieros gamos, since it was associated both with Eros and with the powerful female divinities of the ancient Near East) [46] is shown hovering just above their heads. It holds its own stalk of flowers, which perfectly intersects the cross formed by those held by the king and queen. This is another symbolic prefiguring that refers to the mediating energy, personified as Mercurius, which would function as the third term that would resolve the elements during the final stage.

Plate 3 shows the royal pair naked; wearing separate crowns they again hold out a stalk to each other. They are becoming closer: here each stalk has but one flower, not two, and each of them has reached out to the other to actually grasp the flower which is being proffered. The banner over the king’s head reads: ‘O Luna, let me be thy husband’; that over the queen’s reads: ‘O Sol, I must submit to thee.’ Here again the dove appears between them holding a stalk with a single flower in its beak. The dove’s banner reads: ‘It is the Spirit which vivifies.’

In plate 4 the king and queen become even closer. They are crowned and naked; the dove is between them; the same configuration of stalks with one flower that appears in plate 3 is repeated here, but now they are shown seated within a single vessel filled with water, thereby evoking the commingling of primordial waters, that was already seen in plate 1.

In plate 5 we see the king and queen in sexual embrace.

Plates 6-9 form the first of two series (the second being comprised of plates 13-16) that indicate successively deepening levels of conjunction. The king and queen are shown lying in a sepulcher. They appear for the first time in hermaphroditic form. Their bodies are joined, they have two heads, and they wear a single crown.

It is interesting to compare plate 10 with plate 2, because they are like reverse mirror images. In plate 2 the queen stands on the moon; the king on the sun. They are entirely separate. They wear two crowns. Here, in plate 10 we are shown the end of the process that was illustrated in plates 6-9, which is the alchemical two-in-one. The king and queen are joined to form one perfect winged hermaphrodite. They wear one crown; they stand on a single crescent moon. One serpent coils around her outstretched arm; he holds a chalice from which three serpents emerge. Here I would suggest that the serpent and the chalice are close symbolic kin of the yoni/lingam symbol as it appears in the context of Hindu tantra. In any case, symbolically speaking, in the context of the western alchemical tradition, serpent and cup are often associated with masculine and feminine qualities; the fact that here we see the queen with the serpent, and the king holding a chalice from which three serpents emerge, seems to be a further indication of the progressively deepening exchange. The single face that is shown at the top of the plant heralds the complete conjunction, which is now close at hand.

Plate 11 shows the beginning of the last stage of the work. The image is explicitly sexual. The king and queen, each winged, wear two crowns, and are submerged in water. Their limbs are entwined; her hand grasps his phallus; his left hand fondles the nipple of her breast; his right is under her neck supporting her. Plate 12 shows a winged face of the sun arising from a sepulcher; light (i.e., life) comes from out of darkness (i.e., death).

Plate 13 is the first of four images comprising the second series. Here we see the king and queen in hermaphroditic form, winged, with one crown, lying in a sepulcher filled with water. She is on top. Plate 14 is exactly the same, except here they appear without wings. A female figure ascends into a cloud above them on the upper right. Plate 15 is the same again, except here, the queen is on the bottom, and the cloud now extends across the entire width of the image at the top. It is full of moisture, which falls down in large drops upon the king and queen. Plate 16 is the last in this series of four. Now we see the female figure again, but this time she is descending from the cloud above them on the upper right. The parallelism that can be seen here shows the exchange between masculine/feminine principles that was symbolically depicted in plates 6-9, but on a deeper level than previously.

Plate 17 is like the full flowering of plate 10. It depicts the product of the union between the alchemical opposites. This Child of the Work is not merely the result of a mechanical conjunction of opposites.

Plate 18 shows the lion eating the sun. Symbolically this depicts a stage in the development of the alchemist where the illumination that was previously regarded as outside, “other,” to himself, is now being assimilated into his or her very being. Plate 19 provides an excellent example of the syncretism we often see between alchemical symbols and Christian symbols. Here Mary is in the center, flanked by the Father and the Son, who are about to crown her. The Holy Spirit, in the form of a dove, hovers above. In the background appear the words Tria and Unum, Three and One. [47] This image contains a rich variety of hierogamic themes. First, there is the symbolic similarity between the three waters of the alchemical foundation we saw in plate 1 and the Trinity. Second, the incarnation of Christ, the Second Person of the Trinity, was made possible by the hierogamic union between Mary and the Holy Spirit, the Third Person. Third, the incarnation of the Son entails an ontological condition of simultaneous humanity and divinity–a profound manifestation of hierogamy. Like the marriage between the alchemical opposites, all these unions require mediation. In the alchemical marriage, this function was often performed by Mercurius; in plate 2 we have seen the dove in the role of mediator. Here we see it in that role too, poised above the crown that the Father and Son are about to place on Mary’s head, but now it is explicitly associated with the Third Person of the Trinity. The fact that the dove was a symbolic attribute of the female divinities of the ancient near east underscores the conclusion that plate 19 is also a hierogamic image, albeit in Christianized form.

Plate 20, the last image in the series, depicts the risen Christ. In his left hand he holds a banner marked with a cross; his right gestures toward the now empty sepulcher. That sepulcher unmistakably indicates that the completed alchemical process has involved the transmutation, not merely the transformation, and certainly not the transcendence, of the body. In the view of the alchemist who wrote the Rosarium philosophorum, the Christian doctrine of the resurrection of the body signified not the suppression, or even the transcendence, of the physical body, but its glorification and perfection. If the alchemical work necessitated the transcendence of the body, one would not expect to find an empty tomb, but a tomb filled with the putrefying remains of the king and queen. Instead, we see the risen Christ, the embodiment of the hierogamic union between human and divine. This last indicates a profound change in the subject/object relation since the divine is generally viewed as wholly other to the human.

Tractatus aureum

The Tractatus aureum (The golden tract) was published in 1566, but is traditionally attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. [48] Appended to the first theoretical part is a marvelous story “in which the mystery of the whole Matter is Declared.” It begins with the universal formula of the fairy tale: “Once upon a time,” we read, when I was walking abroad in a wood, and considering the wretchedness of this life, and deploring that through the lamentable fall of our first parents we had been reduced to this piteous state, I suddenly found myself upon a rough, untrodden, and impracticable path . . . [49]

. After finding a group of sages in a meadow and impressing them favorably with his quick wit, in a discussion reminiscent of that which took place between Jesus and the elders in the temple, our protagonist is charged with the task of subduing a magical lion. He accomplishes this feat without delay “by gentle, skillful, and subtle means,” fortuitously combined with a “knowledge of natural magic.” Having finished, he finds himself somehow on top of a wall “which rose more than 100 yards into the air.” With difficulty he proceeds along this wall using a narrow path to the left of a divider that runs along the middle of the wall, and in this way negotiates his path until meeting a person of indeterminate sex, who invites him to try the right side, because it is more “convenient.” Continuing to the end of the wall, he descends by way of a rather perilous route until he enters a place filled with white and red roses. There he discovers a group of beautiful young women, and some rather distressed young men who find themselves unable to reach the women on account of the wall that separates them. Undaunted himself, our hero moves on through a series of gates by unlocking them with a “master key” which he has “diligently fashioned” at some unspecified time in the past. At last he comes to the innermost garden, where he meets a wondrous couple, the most beautiful of all he has seen. He asks the young woman how she had managed to scale the wall and she replies: This my beloved bridegroom helped me, and now we are leaving this pleasant garden, and hastening to our chamber to satisfy our love. [50]

Going on a little further, the protagonist passes a water mill, exchanges some pleasantries with its miller, and stops in front of a platform where there is gathered a group of old men in deep discussion. It seems the men are engaged in a conversation about “a letter which they had received from the Faculty of the University,” and our alchemist knows intuitively that this missive concerns him. He questions the men, who answer that the letter does indeed concern him: [T]he wife whom you married a long time ago,” they tell him, “you must keep for ever or else we must tell our chief.” Since, as he explains, he and his spouse “were born together, and brought up together as children,” he is able to answer truthfully that there is no question of leaving her, and that they will be together even in death. [51]

Next, catching sight again of the gorgeous couple whom he had seen earlier, he notices they are being married properly by the venerable sages, and marvels that the bride, who was also the “mother of the bridegroom,” is so youthful in appearance. But no sooner are these two married than they are accused and convicted of incest, on account of being brother and sister (not mother and son), and are condemned to be “shut up forever in a close prison . . . as pellucid and transparent as glass” (an obvious reference to the alchemical chamber). The door to this chamber is sealed with the official seal of the Faculty, and our friend is given the responsibility of insuring they do not escape, and moreover, of insuring the even temperature of their chamber.

A detailed accounting follows of the mishaps encountered while the alchemist attempts to fulfill this charge. The royal pair have been stripped of their clothes and jewels before being thrust into their prison and readily respond to the earnest (and prayerful) ministrations of their conscientious keeper. We read that, on feeling the warmth, they fall to embracing each other so passionately that the husband’s heart is melted with the excessive ardor of love, and he falls down broken in many pieces. When she, who loves him no less than he loves her, sees this, she weeps for him and, as it were, covers him with overflowing tears until he is quite flooded and concealed from view. [52] There is no doubt whatsoever that the reader is here being instructed in the finer points of the alchemical process itself. And so the story of the coniunctio continues, until the moment when “the rays of the sun, shining upon the moisture of the chamber, produced a most beautiful rainbow,” which gladdens our alchemist immensely. His joy is somewhat dimmed, however, by the sight of the royal pair lying within, apparently lifeless. He does not give up on warning them though, and before long is rewarded by their resurrection. Thus restored to life, they are more beautiful than ever, and soon a second marriage (the alchemical union) takes place. This ceremony is clearly more significant than anything that has gone before. At this point, the alchemist is shown all the treasures and riches of the whole world . . . gold and precious carbuncles . . . the renewal and restoration of youth . . . and a never failing panacea for all disease. [53]

Mutus liber

The Mutus liber (Silent book) was first published in 1677 by Jacob Saulat, and was later included in Joannes Jacobus Mangets Bibliotheca Chemica Curiosa. [54] While many of the images of the Rosarium philosophorum are from the Christian tradition, in the Mutus liber we also find references to the Hebrew Bible (the Christian Old Testament) and to the religious traditions of the ancient Greco-Roman world. Adam McLean points out that the images that are concerned with the specific alchemical processes are enfolded between a first and a last image, which constitute an important reminder about what he calls the “spiritual aspect” of the work. [55] This is quite true, but in my opinion they have another important function as well, which is to provide an unmistakable sign about the beginning and end of the spectrum representing the changes related to the subject/object relation and causality. It is for this reason that my primary focus here will be on the opening and closing images.

The frame within the first plate is oval, a shape that has always been associated with that which gives life, symbolically and literally. This life-giving quality is emphasized by the fact that the oval is comprised of two living branches, knotted together. Each of these branches has many leaves, many thorns, and one rose. The combination of roses with thorns emphasizes the complexity of life, as well as the opposites that must be united in the alchemical work. In the frame, we see a figure lying on the ground sleeping. On the ladder between heaven and earth are two angelsone descending, the other ascendingwho are blowing trumpets by the sleeping figure in order to awaken him. This ladder, a sign of meditation between heaven and earth, connotes Jacobs dream at Bethel (Gen.28:11-12). Jung has commented that this figure represents a person who is

“profoundly unconscious of himself. He is one of the “sleepers,” the “blind” or “blindfolded,” whom we encounter in the illustrations of certain alchemical treatises. They are the unawakened who are still unconscious of themselves, who have not yet integrated their future, more extensive personality, their “wholeness,” or, in the language of the mystics, the ones who are not yet “enlightened.” [56]

This observation underscores the traditional esoteric meaning of Jacobs ladder. Before Jacob went to sleep, he did not know the sacrality of the place, but when he awakened, he did. His subsequent naming of the place (formerly Luz) was thus an intentional (i.e., cognizant) act of cosmicization. [57] Furthermore, again in keeping with the esoteric meaning of Jacobs ladder, such an awakened one becomes responsible for the function previously exercised by the angels; i.e., helping others awaken. Now, Jacob is one who sees. With respect to the subject/object relation, we see that here, at the outset, the usual understanding of the subject/object relation prevails. Heaven is above, and separated from the earth; the divine is separated from the human. The ascending angels and the ladder symbolically represent the means of connection between these spheres; it is here a mediated connection. This symbolism, together with the two branches bearing thorns and flowers that are tied together, refers to the alchemical oppositions that will be resolved; it also tells us something about the initial understanding of causality. When we have two material objects that we want to join, we use glue, or nails, or, as pictured here, we tie them together with a knot. In other words, a mechanical means is used to join two things that are separate. A clear distinction is made between the means or method of performing an action and the thing that is the object of the action. Mechanistic causality is precisely what is symbolized for us here.

The above and the below are represented in the second image, which is divided into to distinct sections. At the bottom we see the actual condition of the alchemical couple as they are about to begin the work. The ideal, or potential condition is imaged in the uppermost frame. The alchemical pair is shown winged, i.e., idealized, holding an alembic within which we see Jupiter and a pair of children, one solar, the other lunar. [58] At this stage, the ideal condition that is imaged is regarded as “other” relative to the present. It is the Goal of the Work, which they can hope to reach only after a long and arduous series of tasks.

The third image is an imago mundi, showing the macrocosm. In the fourth image we see the couple gathering the morning dew. Adam McLean’s interpretation of this image focuses on its significance in terms of the “etheric forces” which are associated with the earth as it goes through seasonal change. I am also reminded of the connection between common dew, and the alchemists’ repeated insistence on the ordinary nature of the substance that was needed for the work: it is something that is “walked on, children play with it.”

Images 5 through 14 show successive stages of the work in the laboratory. While comments on each of these would take us too far from the present focus, it should be noted that these images too, just like those in the Rosarium philosophorum, are symbolic of a hieros gamos. Although never explicitly sexual, as are many of the images in the Rosarium, these two show a series of deepening exchanges between the alchemical pair, sometimes with Mercurius appearing as the third enlivening and enabling term. That they are combined here with what could conceivably be construed as directions for actual laboratory work is, in my view, a further indication of the most profound level of hierogamic process. As the Tabula smaragdina advises, The strength of it is complete only if the powers of upper and of lower are combined. That is, heaven and earth must be joined.

In the last image, the ladder is discarded and lies on the ground. The central part of a winged, organic form emerges from what had formerly functioned as a knot tying the two branches together in a mechanical way. Now the joining is organic, not mechanical. The branches no longer have thorns, but berries. They still form an oval, but here it is wide open at the top; in the center of the sky above them is a sun, with a beneficent, smiling face; its rays extend from all around it. The couple that has worked together throughout the work join hands; banners come out of their mouths that say: “[P]rovided with eyes thou departest” (oculatus abis). [59] The figure of Zeus is above them. He stretches a tasseled cord between his hands with the ends hanging down; each of the pair has reached up to grasp one of the tassels. This image reflects an understanding and an experience of the universe as being ontologically whole, which arrives at the end of a long process involving the dissolution of an entire framework that had functioned to support an understanding and experience of separation.

Closing Reflections

The central theme in the Mutus liber, the Aureum saeculum redivivum, and the Rosarium philosophorum, is that of the alchemical conjunction of opposites, imaged under the form of a hieros gamos. In the alchemical tradition the hieros gamos images represent the process of sacralizing the profane, of cosmicizing chaos, of actualizing that which had been previously potential. In the course of writing this paper and thinking about these texts it occurred to me that a fruitful topic for further exploration would be to consider whether the alchemist and his Soror mystica were intended to be primarily (or exclusively) symbolic representations of an interior process. This is particularly important in view of the fact that the alchemists placed so much emphasis on actualizing the potential, on leading out the gold, as they often said.

While commenting on the parts played by the alchemical pair in the Mutus liber Jung states:

[T]he artificers . . . in the symbolical realm are Sol and Luna, in the human the adept and his soror mystica, and in the psychological realm the masculine consciousness and the feminine unconscious . . . The two vessels are again Sol and Luna. [60]

With respect to the exteriorization or actualization of the inner condition, he notes that

Classic pairs are Simon Magus and Helen, Zosimos and Theosebeia, Nicholas Flamel and Peronelle, Mr. South and his daughter (Mrs. Atwood, author of A Suggestive Enquiry into the Hermetic Mystery) . . . The Mutus liber . . .represents the Mysterium Solis et Lunae as an alchemical operation between man and wife.” [61]

The nature of the conjunction seems to me to suggest that the tradition of the alchemist and the Soror mystica was not simply intended as a symbol with no corresponding reality in time and space, but that it was a form of Western tantra. However, to explore such speculation would go far beyond the scope of the present article. It would require a book to do justice to the different aspects of the symbolism of the alchemical coniunctionis and the various significations that have been accorded it, and perhaps someday such a book will be written. For the moment we can say that, in general, the attempt to achieve the alchemical conjunction seems to have entailed a relentless striving for perfect congruity between the interior condition of the alchemist and the outer world. As sensible people we know that perfect congruity is impossibly idealistic and perhaps we might even go so far as to call it impossibly utopian. Yet if one were an alchemist, this would nevertheless be the ideal toward which one would ceaselessly try to move. Here I recall something that Mircea Eliade wrote about his study of tantric texts.

The Sun and Moon must be made one . . . above all prajna, wisdom, must be joined with upaya, the means of attaining it. . . all this amounts to saying that we are dealing with the coincidentia oppositorum achieved on every level of Life and Consciousness. [62]

Idealistic or not, it would appear that the actualization of the “coincidentia oppositorum on every level of Life and Consciousness” as Eliade put it, was the thing which would obsess the alchemists until their dying breath. Certainly this would have entailed radical changes in both the conception and the experience of the subject/object relation. Does this mean that the tradition should be dismissed because of the presence of what some contemporary psychiatrists might call a manifestation of obsessive compulsive behaviors, mixed with psychological inflation and delusions of grandeur? When viewed from such a perspective, spiritual alchemy certainly could appear to be only that. But then, we could also say that the same thing was manifested by the great spiritual teachers. In my view, in its purest form, spiritual alchemy constitutes a bona fide tradition within the history of religions, one that represented a serious hope that it was possible to overcome the subject/object dichotomy, that chasm which seems to yawn between the spirit and the body. As such, its praxis focused on making the impossible, possible. [63] Spiritual alchemy may well have been an obsession, but I submit that it was a truly magnificent obsession.

* * *

Karen-Claire Voss

August 1994

Istanbul

[1] Mircea Eliade cautions against conflating the method and raison d tre of alchemy with that of prechemistry in Alchemy as a Spiritual Technique in Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, 2nd ed., Bollingen Series 55 (Princeton, 1969), 290-92. For an excellent contextualization of alchemy within the esoteric tradition, see Antoine Faivre, Access to Western Esotericism (Albany, 1994). Cf. idem, “Ancient and Medieval Sources of Modern Esoteric Movements,” in Modern Esoteric Spirituality. Antoine Faivre, Jacob Needleman, and Karen Voss (New York, 1992), 1-70.

[2] Antoine Faivre, “Esotericism,” Hidden Truths: Magic, Alchemy, and the Occult, edited by Lawrence E. Sullivan (New York, 1987), 41.

[3] The earliest textual evidence of alchemy dates from about the second century B.C.E. See E.J. Holmyard, Alchemy (Harmondsworth, 1957), 25; and Rudolf Bernoulli, Spiritual Development as Reflected in Alchemy and Related Disciplines, in Spiritual Disciplines; Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks, Bollingen Series 30, 4 (New York, 1960), 308. An excellent overview of alchemy is F. Sherwood Taylor The Alchemists (1951; reprint, London, 1976). Al, meaning the, comes from the Arabic; kimia may be derived from the Egyptian kmt or chem., meaning black land, or from the Greek chyma meaning to fuse or cast metal. See Holmyard, Alchemy, 19.

[4] See Eliade, The Terror of History, chap. 4 in Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return (New York, 1959), 139-59. The best exposition of the hermenutical significance of the alchemical traditon is still Mircea Eliades The Forge and the Curcible: The Origins and Structures of Alchemy (Chicago and London, 1978). Also noteworthy is Franoise Bonardels breathtaking Philosophie de lalchimie; Grande oeuvre et modernit (Paris, 1993).

[5] Robert Darnton, Mesmerism and the End of the Enlightenment in France. (Cambridge, 1968), vii-viii. See also Allen Debus’s introduction to the 1967 reprint edition of Elias Ashmole’s Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum (New York and London, 1967), which calls for us to “make the attempt to place ourselves within the intellectual climate” of the late seventeenth century.

[6] See Antoine Faivre, Renaissance Hermeticism and the Concept of Western Esotericism, in this volume. See also Antoine Faivre and Karen-Claire Voss, “Western Esotericism and the Science of Religions,” Numen 42 (1995), for a summary of the components of esotericism.

[7] On the use of the term imagination here, see Marie Louise von Franz, Alchemical Active Imagination (Dallas, Texas: Spring Publications, 1979). Cf. Henry Corbin, “Mundus Imaginalis or the Imaginary and the Imaginal” Spring (1972), 6-7, for a discussion of the mundus imaginalis as “a very precise order of reality, which corresponds to a precise mode of perception.” For a comprehensive and extraordinarily sensitive analysis of the use of imagination in mysticism, see Corbin, Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn Arabi, translated by Ralph Manheim. Bollingen Series XCL (Princeton, 1969). First published as L’Imagination cratrice dans le Soufisme dIbn Arabi (Paris, 1958). Parts One and Two were originally published in the Eranos-Jahrbcher XXIV (1955) and XXV (1956) (Zurich).

[8] Exemplars of that tradition set great store by the works belonging to the Corpus Hermeticum. Written by different authors between 110 and 273 of the common era, these texts were all attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, who can be regarded as a kind of patron saint of alchemy, since he is invoked repeatedly, and since his mercurial presence, in one guise or another, is recurrent. For a discussion of the esteem in which Hermes and these texts were held during the Renaissance, see Karen-Claire Voss, “Three Exemplars of the Esoteric Tradition in the Renaissance.” Alexandria: the Journal of the Western Cosmological Traditions 3 (1995). For Hermetic images in the alchemical tradition, see C.G. Jung’s memorable characterization of the alchemical Mercurius as the “paradox par excellence,” in Mysterium Coniunctionis, Bollingen Series II (New Jersey, 1968), 43, et passim.

[9] Two examples that come to mind are Jacob Boehme’s pewter vessel and Julian of Norwich’s hazlenut. Cf. Mircea Eliade’s discussion of hierophany in The Sacred and the Profane. Trans. from the French by Willard R. Trask. (New York, 1959), 11-12.

[10] See Antoine Faivre, Pour une approche figurative de alchemie, in Mystiques, Thosophes et Illumins au sicle des luminres. (Paris, 1971; reprint, Hildesheim and New York, 1976). In my view, this is one of Faivres most theoretically interesting works.

[11] One could also think of scholars such as Rudolf Otto, Gerardus van der Leeuw, or Rudolf Bernoulli. I note that in Faivres article Pour une approche, a propos of praising Mircea Eliade he emphasizes that a historical perspective by itself is not adequate for dealing with phenomena like that of alchemical transmutation (202). In the same article, he also states that il neest pas possible de negliger lhermeutique spirituelle while studying alchemy and related topics (212).

[12] Leo Stavenhagen, editor and translator, A Testament of Alchemy. Being the Revelations of Morienus to Khalid ibn Yazid. (Hanover, New Hampshire, 1974), 66.

[13] Faivre, Pour une approche, 201.

[14] See Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane, 189, for a description of the initiate as one who has experienced the mysterieswho knows.

[15] See Favire, Pour une approche, 201 n.2; and John Read, The Alchemist in Life, Literature and Art (London, 1947), 29. Of course, the separation between material and spiritual alchemy, was not in fact so rigid. An alchemists conception and experience of the work would change as progress was made, although this change seems to have occurred in only one direction; i.e., a material alchemist would become a spiritual alchemist. See also Eliade, Yoga, 289-90 for a discussion of the distinction between esoteric and exoteric alchemy, which has a sense analogous with the distinction made here between material and spiritual alchemy.

[16] The present articulation of these three characteristics represents a further theoretical description of work begun in my masters thesis (Aspects of Medieval Alchemy: Cosmogony, Ontology, and Transformation [diss., San Jose State University, 1984]). A work in progress is devoted to further development of the issues that are discussed in this article: e.g., taking serious account of the ontological aspect of the experience of transmutation, examining the changing conception of the subject/object relation, causality, and time. In that work, I also discuss another change, i.e., in the conception of energy. I argue that material alchemy essentially conceives of energy and power as things that can be possessed, contained, directed; in material alchemy we think in terms of manipulation, of domination, sometimes even of destruction. In contrast, in spiritual alchemy energy is not approached as a possession, or as something to be used, but as a kind of gift. Energy is therefore experienced and understood as essentially transformative, creative, enabling. Nothing needs to be done with it, or because of it, or with it; power is noted as a fact. What is required is that one serve the gift.

[17] See Giordano Bruno, Cause, Principle, and Unity, translated and edited, Jack Lindsay (Westport, 1962), 82.

[18] See note 16.